Mallorca hotels and prices - don’t forget the costs

Delayed because of Covid, hotels are now looking at a further 3.5% salary on their labour costs

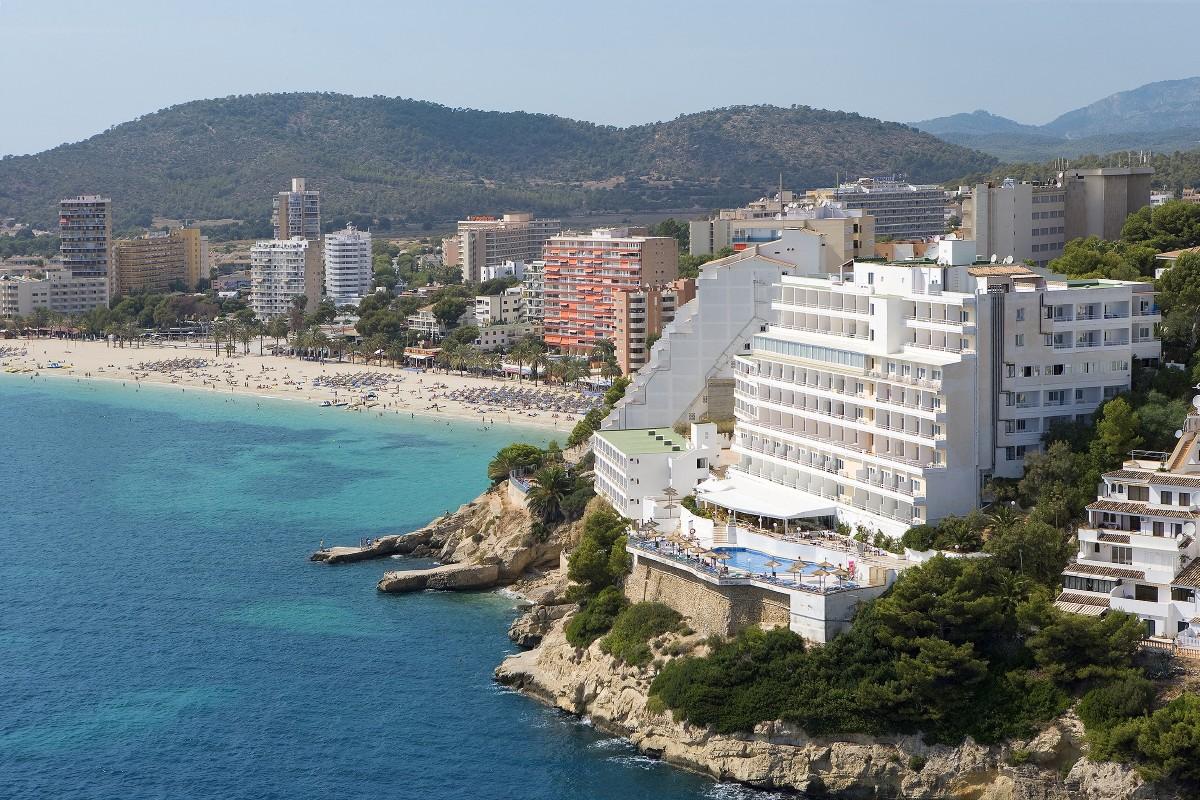

The pandemic, which came hard on the heels of the Thomas Cook collapse, created its own liquidity challenges | E.C.

Palma01/04/2022 11:57

Stating with certainty that a hotel’s profit margin should be X% would be ridiculous. It depends on various factors and it will vary accordingly. This said, there are the experts who can point to ballpark margins. As an example, PKF Consulting quotes a figure of thirty per cent. This is an average, recognising that the amount of revenue left over after accounting for expenses will fluctuate. So it could be 20% or it could be 40%. It all depends.

Also in News

- As Spain says adios to Golden Visa, Portugal says come on down!

- Here comes the sun - Mallorca weather forecast for Easter

- Mallorca holiday paradise vanishing for some German tourists

- Truck gets stuck in Mallorca village

- Tens of thousands of Mallorca-bound British tourists facing long air delays this summer, airline boss warns

No comments

To be able to write a comment, you have to be registered and logged in

Currently there are no comments.